This is an aspect of history and politics that I am particularly passionate about. The antebellum and Civil War eras are by far my favorite part of United States history. While I normally see politicians as corrupt individuals who take advantage of their positions of power, Lincoln is a politician who I really do respect, which is why I consider him to be my favorite U.S. president. I will admit that I am slightly biased in favor of Lincoln, but I also find it critically important to approach his legacy in a holistic and objective manner that does not leave out or ignore his flaws and shortcomings.

Before we get into Lincoln’s track record, I want to emphasize that I will be going in depth specifically on the issues of slavery and racial equality. There are certainly other characteristics of Lincoln that are worth analyzing, such as his tremendous leadership and resilience during the Civil War. But for the purposes of this article, I will be zeroing in on Lincoln’s record on race relations in America, particularly on the question of slavery.

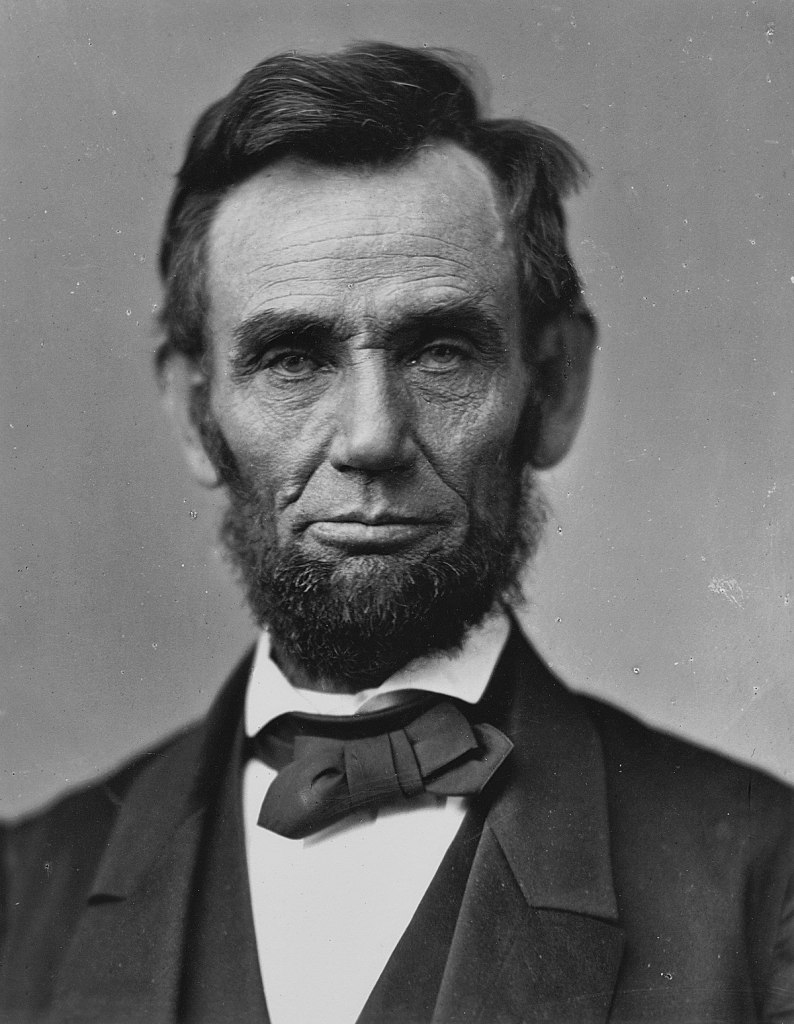

How should we view Lincoln today? Is he really the Great Emancipator that many Americans make him out to be? Or have we painted an inaccurate, overly sympathetic image of who Lincoln really was? What can we conclude about his role in major historical developments, particularly the abolition of slavery and the advancement of African-American rights in 19th-century America?

To understand the answers to these questions, we need to take a close look at Lincoln’s entire political career, not just his presidency. Many people are unaware of this, but Lincoln served in the Illinois state legislature and the U.S. House of Representatives, well before he was elected President of the United States. It is important that we examine Lincoln’s beliefs on slavery throughout the entirety of his political career, not just his tenure in the White House. Now, what exactly were those beliefs?

Lincoln was strongly against slavery from a moral standpoint. No questions asked. There was never a time in his political career when he wavered on his condemnation of slavery as a moral disgrace, arguing that it was “founded on both injustice and bad policy.” Here are a few quotes to show Lincoln’s opinions on slavery:

“I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel.”

“I have always hated slavery, I think as much as any abolitionist.”

“Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.”

The Illinois state legislature emphatically passed a resolution condemning the abolitionist movement, with an overwhelming 77-6 majority. Abraham Lincoln was one of those six people. That must mean that Lincoln was an abolitionist, right? Well, not quite.

Lincoln was firmly anti-slavery from a moral perspective, but that did not make him an abolitionist politically. In antebellum America, abolitionism was the belief that slavery anywhere in the United States should be ended totally and immediately, no matter where it existed. Lincoln, on the other hand, was nothing more than an anti-slavery advocate (at least at this stage in his life). This brings up our next major question: how could Abraham Lincoln be anti-slavery without being an abolitionist? This is a critical question that many Americans get wrong.

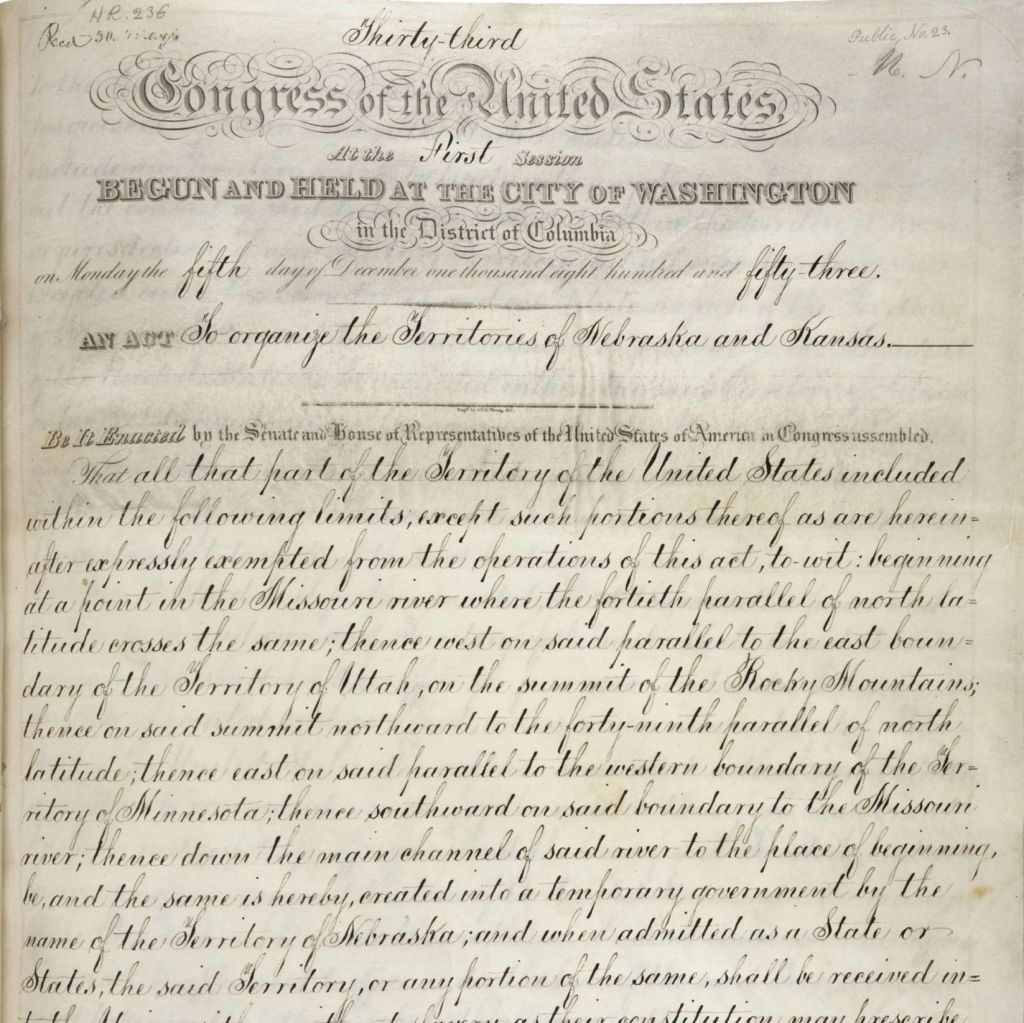

During Lincoln’s time, America was expanding. The Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican Cession (the latter resulting from the Mexican-American War) allowed the U.S. to gain huge amounts of new territory in the West. As the land was being settled, it set off a bitter national debate over the extent to which the institution of slavery should be limited, expanded, protected, or abolished. Lincoln had a nuanced anti-slavery approach. Despite his moral objections to slavery, he argued that the institution should only be prohibited from expanding to newly gained territories, but it should not be wiped out in the Southern states where it already existed. This explains why he fiercely opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, as well as the infamous Dred Scott Supreme Court ruling, which both legalized the potential expansion of slavery. Take a look at the following quote from an Illinois speech that Lincoln gave in 1854, six years before he was elected president:

“I wish to make and to keep the distinction between the existing institution [slavery], and the extension of it, so broad, and so clear, that no honest man can misunderstand me, and no dishonest one, successfully misrepresent me.”

Essentially, he was against the expansion of slavery, but he was not in favor of universal abolition. This is an important nuance that complicates Lincoln’s stance on the slavery question.

Now that we understand Lincoln’s exact position on slavery, we must face an important question that is so critical to evaluating Lincoln’s legacy: if Lincoln made his opinions clear on how slavery was a morally abhorrent institution, then why would he limit himself to only being against the expansion of slavery? Why not be an outright abolitionist? This next part is what makes Lincoln such a compelling character and politician.

Ardent defenders of Lincoln paint him as a moral paragon, but some of them leave out an important aspect: Lincoln was a shrewd politician who knew how to navigate his way through political obstacles that stood in his way. Despite his opposition to slavery as a moral evil, he believed that an abolitionist stance was not the most effective approach on practical grounds, saying that “the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its [slavery’s] evils.” In addition, as a former lawyer and a strong supporter of the U.S. Constitution, Lincoln believed that the government must act within the four corners of the law. He believed that the Constitution prohibited the federal government from immediately abolishing slavery in the states where it already existed. In a sense, he believed that slavery was to an extent protected by the Constitution. This is why a fervent abolitionist like William Lloyd Garrison hated the Constitution, calling it “an agreement with hell.” Garrison even publicly burned a copy of the document!

At this point in time, Lincoln felt like the best way to dismantle the evil institution of slavery, without breaking his oath to the law and to the Constitution, was a moderate anti-slavery approach. First stop its expansion, then work towards policies of gradual emancipation that would slowly but surely free the remaining slaves in the states where the institution already existed.

He also argued that the Founding Fathers did not intend for slavery to be expanded or perpetuated forever as a sacred right in the United States. Let’s take another look at that speech that Lincoln gave in 1854:

“Thus, the thing [slavery] is hid away, in the Constitution, just as an afflicted man hides away a wen or a cancer, which he dares not cut out at once, lest he bleed to death; with the promise, nevertheless, that the cutting may begin at the end of a given time.”

This quote perfectly encapsulates Lincoln’s approach to the slavery question: there is no doubt that he wanted the institution gone, but total and immediate abolition was not the most practical approach, nor was it sanctioned by the law of the land. He approached the eradication of slavery the same way that a doctor would approach a cancer patient: first stop the spread of the cancer before it becomes deadly. Then slowly but surely eradicate the disease until it is fully gone.

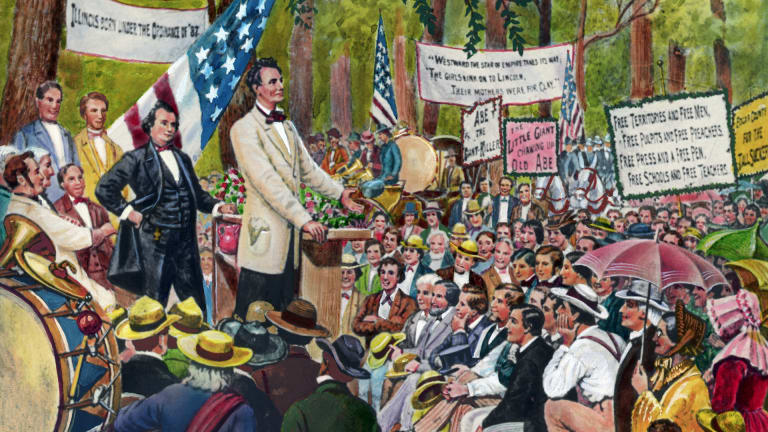

When discussing Lincoln, it is important that we also highlight his flaws, particularly when it comes to his views on race. In the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, he did argue that “there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” and that “he [the black man] is as much entitled to these [rights] as the white man.” However, he was certainly no saint when it came to his views on race relations. When put on the spot by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a viciously racist Democrat, on whether he believed in racial equality, this was Lincoln’s response:

“I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races [applause] … there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. I, as much as any other man, am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

Not the typical view that we have of the Great Emancipator.

On top of that, he argued that because of such strong anti-black racism in the white community, there was no way that white people would allow black people to live among them as equals in society. This was the basis for his ideas of colonization:

“If all earthly power were given to me … my first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia—to their own native land.”

These were Lincoln’s personal views. But he felt that colonization was not possible from a practical perspective. In addition to prohibiting the spread of slavery, his politically pragmatic argument was to gradually emancipate the remaining slaves, which would allow for a controlled management of “free negroes.”

Many people, especially the strongest defenders of Lincoln, argue that Lincoln was still a man of his time. They assert that it would be unfair to expect a mainstream political candidate to support racial equality in a time when it was considered to be so radical. It is very possible that Lincoln said this as a political strategy to gain votes, especially since Douglas accused him of favoring black people too much. Had he openly stated his support of racial equality in the social and political context of his time, he would not have survived as a politician. Almost no one at the time would support someone who advocated for equality of the races.

While Lincoln’s racist views are indefensible in and of themselves, it is important to understand that Lincoln was an astute politician who had to moderately express his anti-slavery views without alienating his voters. Lincoln had to appeal to racist white Northern voters, so advocating for racial equality could have doomed his political career. Lincoln was a moderate man who followed a path of gradual progress rather than radical change. The nation was hardly ready for racial freedom (emancipation from slavery), let alone racial equality (social and political equality between black people and white people). Lincoln was a shrewd operator who took a very calculated and politically practical approach to dismantling the institution of slavery.

While this may have been a political strategy to win the support of racist white Northerners, it is also very possible that Lincoln genuinely believed in these racist ideologies. One could argue that Lincoln was most definitely a racist man. Afterall, this was the 1850’s, where just about everyone was a bigot by today’s standards.

Now that we have a good understanding of Lincoln’s views prior to being elected president, this brings us to the final and most significant part of his political career: how did Lincoln approach his role as commander-in-chief regarding the issues of slavery and race relations, particularly during the crisis of the Civil War?

For the first couple of years of his presidency, Lincoln was hesitant about making the war about slavery. He prioritized the survival of the Union over the future of slavery. Horace Greeley, an abolitionist and fellow Republican, demanded that Lincoln do something about the evil institution. Take a look at Lincoln’s response in an 1862 letter, during the heart of the Civil War:

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union.”

Many critics of Lincoln use this quote to argue that he never truly cared about freeing the slaves, and that his only true objective was to win the war. However, I argue that this is an inaccurate assessment of Lincoln’s political goals and legacy.

There is no denying that at this point in the war, he prioritized the preservation of the Union at a time when the nation was tearing itself apart. However, to say that Lincoln had no interest in freeing the slaves is simply ahistorical. Lincoln was hesitant about making the war about emancipating the slaves because he feared that it would alienate Northerners and Unionists that he so desperately needed for the war effort. But his ultimate goal remained: he wanted slavery abolished in the long-term. Take a look at what he said just a few sentences later in that same 1862 letter to Horace Greeley:

“I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty [prioritizing the saving of the Union]; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.”

While Lincoln was careful about slavery on practical grounds with the situation of the war, his personal desire to eradicate slavery at some point in the future (which he would ultimately accomplish a few years later) never wavered.

So, what changed? Why did Lincoln shift to making the war about slavery? Well, unlike what many people think, it involved much more than just his personal anti-slavery sentiment.

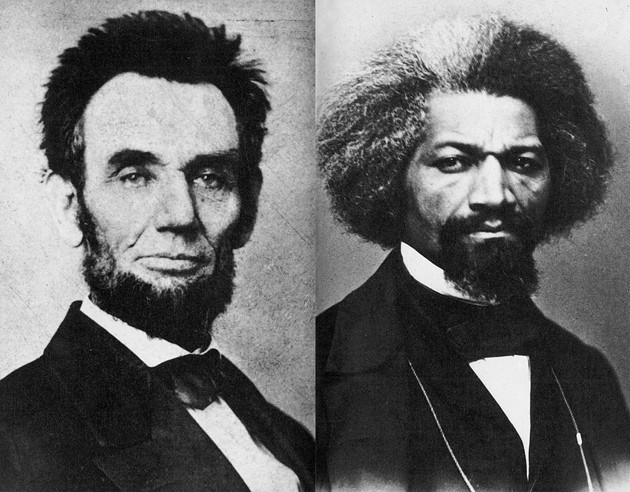

Slavery was the foundation of Confederate society. It kept the Confederate army on the battlefield. With the convincing of Radical Republicans and abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass, Lincoln realized that attacking slavery would be an effective war strategy in undermining the Confederacy. This is what motivated Lincoln to transform the war into a fight to end slavery, rather than only to preserve the Union. This was the basis for his issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation, one of the highlights of Lincoln’s political career. But we must take a close look at a key part in the Proclamation:

“And upon this act [freeing the slaves in Confederate territory], sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.”

The phrase “upon military necessity” is crucial to understanding the significance of Lincoln’s Proclamation: it was a practical war measure that he believed would help bring the Union closer to victory. This is a major talking point of Lincoln’s harshest critics who argue that Lincoln’s Proclamation is “overrated.” They assert that the Proclamation was a mere war measure, not a moral desire to emancipate enslaved people.

It is true that Lincoln issued his Proclamation because he believed that freeing the slaves (at least those in rebel Confederate territory) would be the best strategy to win the war. However, to say that it was 100% out of military necessity would totally ignore Lincoln’s entire anti-slavery life. For his whole political career (since decades before he was elected president), Lincoln always stood firm in his moral opposition to the institution of slavery. Even though he was not an abolitionist for most of his political career, he always had the intention of seeing the eventual demise of slavery, even if that meant taking a more calculated, politically practical approach to achieving that moral goal. As Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer said, “you cannot achieve moral goals without a political opportunity.” The war was the political opportunity, and the Proclamation was the moral goal. Any other politician at this time could have been so committed to the ideology of white supremacy that they could not bring themselves to free the slaves. However, Lincoln, a robust anti-slavery advocate who argued for the natural rights of black people (but not social and political equality), was willing to issue the Proclamation that any other politician would not be willing to do.

As Lincoln’s reelection campaign was around the corner in 1864, Lincoln was still hesitant about supporting the increasingly popular abolitionist movement. He feared that he may alienate the moderate and conservative factions of the Republican Party. However, as had often been the case with Lincoln, he changed his mind.

By the time he was renominated by the Republican Party and entered the 1864 presidential election, he ran on a platform of the universal abolition of slavery by constitutional provision, which would become the 13th Amendment. Lincoln felt incredibly grateful towards the African-Americans who had served in the Union army. He felt that the nation was in debt to them and that they deserved their freedom. After decades of moderate views on the issue of slavery, Lincoln was now a full-fledged abolitionist.

It is important to note that Lincoln did not become an abolitionist on his own. He had always been a moderate anti-slavery advocate on politically pragmatic grounds. But with the convincing of abolitionists who were more radical than him, he slowly but surely moved his way towards a stance of total abolition. The Emancipation Proclamation was a step in the right direction, but his support of the 13th Amendment as the leader of the Republican Party in 1864 remains a great part of his legacy.

But an even greater part of his legacy was what he got done after being reelected. Unlike most politicians, he delivered on his promises by taking action.

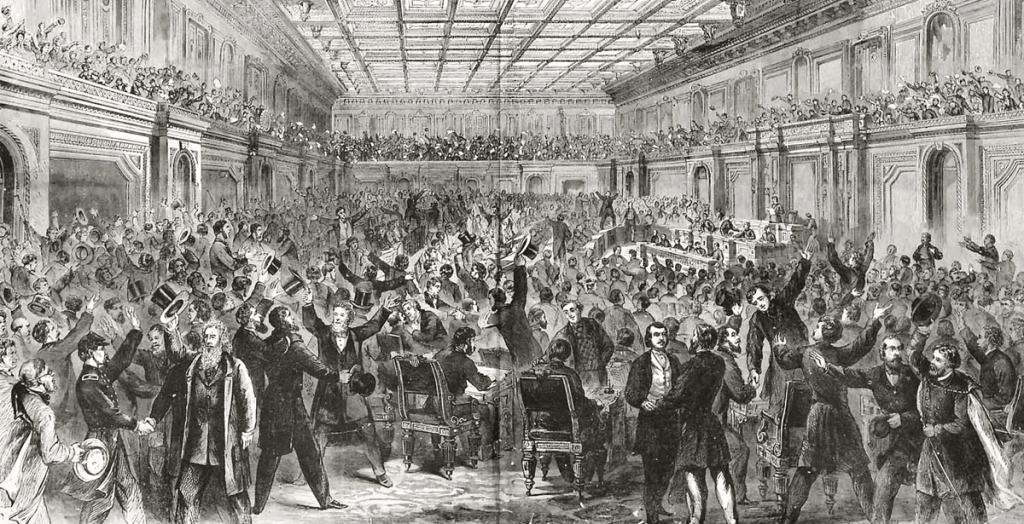

Constitutionally speaking, amendments are solely the responsibility of Congress and state legislatures. The president does not formally get a say in the proposal or ratification of an amendment. Despite these limitations, Lincoln undertook a monumental effort of political persuasion to get as many votes as he could in the House of Representatives in order to get the 13th Amendment passed in Congress. The passing of the great abolition amendment demonstrated a remarkable change in the course of Lincoln’s political career. This accomplishment debunks the idea that Lincoln only cared about slavery for the war effort. If Lincoln had only ever cared about winning the war and preserving the Union, then why would he fight for the 13th Amendment even after he had secured the Union’s triumph in the Civil War?

However, in no way was this change sudden or radical. Lincoln approached the issue of slavery from a politically practical perspective that allowed him to slowly but surely dismantle the evil institution of slavery. He gradually moved in the right direction, without making huge strides of progress all at once. While some consider this to be a criticism of Lincoln, I find it to be a great illustration of Lincoln’s evolution on the issue of slavery, as well as his political savvy. Once the political opportunity presented itself, Lincoln took that step towards abolishing slavery, which had always been his ultimate long-term moral goal, even if he had not always been an abolitionist on political grounds. One might say that he only supported abolition because he was pressured into it. But this logic completely ignores Lincoln’s moral opposition to slavery from the beginning. There was certainly political pressure, particularly from Radical Republicans and abolitionists, but only an anti-slavery politician like Lincoln would consider these calls for abolition.

Soon after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House and the Civil War came to a close, Lincoln took his political ambition one step further: he argued that newly freed black men should have limited voting rights. He believed that black men who served in the Union army, as well as “very intelligent” (i.e. literate) black men, should be allowed to vote. Keep in mind, Lincoln used to be totally opposed to black people voting. He had made that clear in his debates with Stephen A. Douglas. Despite his limits on the idea of black men voting, this was an extraordinary step in the right direction, and it was considered extremely radical for his time. This new view of Lincoln is what ultimately got him assassinated. John Wilkes Booth, a viciously racist Confederate sympathizer, vowed to kill him for his support of “n***** citizenship.”

I find Lincoln’s story quite incredible. Just take a look at his evolution as a politician. This man went from a moderate anti-slavery advocate (while still being against racial equality and in favor of sending former slaves back to Africa) to a full-on abolitionist who was now in favor of opening up the polls to black people. Lincoln was a great man in the course of history not because he was a perfect politician who always said and did the right things; rather, he progressed over time and achieved moral goals despite his imperfections as a politician and as a man. Take a look at what W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the founders of the NAACP, said about Lincoln:

“I love him not because he was perfect, but because he was not and yet triumphed … The world is full of people born hating and despising their fellows. To these I love to say: See this man. He was one of you, and yet he became Abraham Lincoln.”

This quote from historian Louis Masur perfectly captures the essence of Lincoln’s legacy:

“Lincoln was evolutionary. And in being evolutionary, he became revolutionary.”