The United States of America is known for its democratic form of government in which the people have a strong say in who runs their country. But if you look at how we elect our president, it is hard to argue that we have a true democracy. One could even argue that our presidential elections are inherently undemocratic, and this is largely due to the system of the Electoral College.

Understanding the historical background of the Electoral College is key to the debate on whether we should keep it as it is, reform it, or completely abolish it.

How exactly does this system work, and where does it come from? America is a democratic republic that functions differently compared to other democracies. The people do not directly vote for the president; rather, they play an indirect role in choosing their leader.

The non-Congressional electors of each state, who make up a legislative body called the Electoral College, are the ones who directly elect the president. They are expected to vote in accordance with the popular vote of their state, but they are not required by law to do so. Electors who do not vote for the candidate that the people of the state voted for are called faithless electors.

When you vote, you are basically hoping for the popular vote of your state to be in favor of the candidate that you are voting for, since this would result in your state’s electoral votes being given to that candidate. Your vote is not counted toward a national tally. In fact, your vote ends up meaning nothing if the state votes against your candidate.

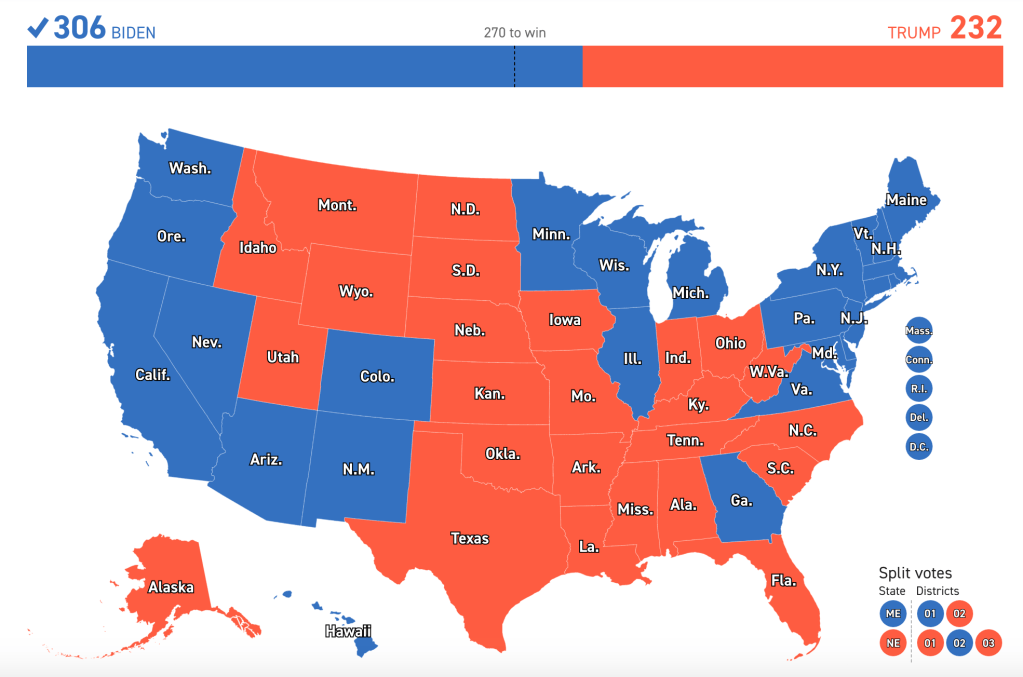

Every four years on election day in November, we see these random numbers on TV, such as “538 electoral votes” and “270 votes to win!” But where do these numbers come from? We have to go back to the nation’s founding to fully grasp how our electoral system works.

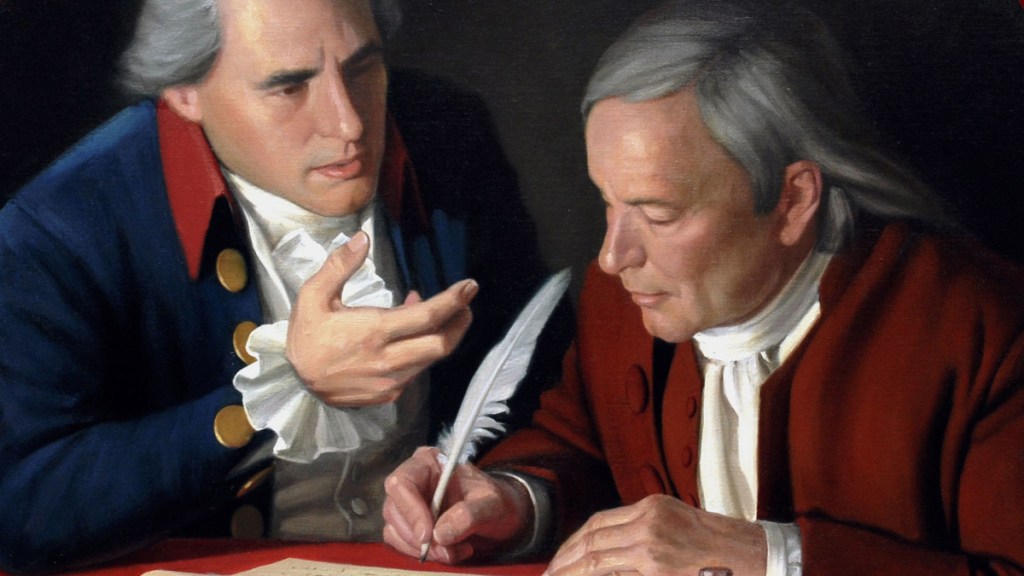

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia was a hotspot of fiery political debates over how the new nation should be governed. One of the most contentious arguments in the Convention was how the president should be elected. The delegates simply could not agree on a solution to the problem. Some believed in a national popular vote, but this idea was met with fierce resistance from those who feared giving too much power to the people. As a result, they ended up devising a peculiar system that would serve as a compromise between rivaling factions within the Convention. We can see here that the Electoral College was in no way an ideal plan that everyone in the Convention was enthusiastically on board with. Rather, it was more of a glued-together solution to one of the many conflicts that consumed the Convention. The Electoral College was necessary for the ratification of the Constitution and the preservation of the Union in its early years.

There were a few reasons why the Founding Fathers feared giving the people too much power in choosing their leader. America in 1787 was extremely divided. There was no real “national politics” in which people were aware of what was going on in other parts of the country. The Framers believed that ordinary people would not have the resources to be properly informed about the candidates or national politics as a whole. They also feared a potential “democratic mob” that could steer the country into chaos. Lastly, a president appealing directly to the people could command dangerous amounts of power, as would later be seen with tyrants like Nazi Germany’s Adolf Hitler.

Many people do not realize that the Electoral College is based on the exact same reasoning used for representation in Congress. Let’s take a look at a few more important aspects of what was going on in Philadelphia in 1787.

Representation in Congress is based on a few different plans that were presented at the Convention. The Virginia Plan argued that the number of delegates in Congress that each state receives should directly correspond to the population size of that state. The New Jersey Plan argued that each state should get equal representation in Congress regardless of that state’s population size. The reasoning behind this plan was to prevent states with highly populated cities from overpowering states that had more rural areas with lower population sizes. The bicameral legislature in Congress that we have today is based on the Great Compromise (also known as the Connecticut Compromise), which is a merging of the Virginia and New Jersey Plans. The House of Representatives is based on the Virginia Plan, in which the number of delegates for each state corresponds to the state’s population size. The Senate, on the other hand, is based on the New Jersey Plan, in which each state gets two senators no matter its population size.

The electoral votes in the Electoral College are based on representation in Congress. For example, Florida has two senators (just like every other state) and 27 members in the House of Representatives, which is why Florida receives 29 electoral votes (2+27=29). This same logic is applied to every state. Modern elections have a total electoral count of 538 votes (535 members in Congress, plus 3 electoral votes for Washington, D.C.). This is why 270 is the “magic number,” as this gives a candidate a majority of the electoral votes. Those 270 votes, not the national popular vote, is what awards a candidate the presidency.

Now that we understand how the Electoral College works, as well as the history behind it, let’s analyze the arguments on both sides of the debate. Should we keep the Electoral College as it is? Or is it an outdated system that needs to be replaced with a national popular vote? Perhaps there could be some middle ground? I would like to present the strongest arguments from each perspective, starting with why we should keep the Electoral College.

Despite the virtues of democracy in giving “power to the people,” it has its flaws. A direct democracy in which “majority rules” opens the door to demagogues who are capable of convincing the masses to support them, regardless of their true qualifications as a candidate. Thomas Hobbes, a supporter of the U.S. Constitution, referred to direct democracy as nothing more than an “aristocracy of orators.”

While democracy in its ideal form is the best system of government, the Electoral College acts as a protective barrier against the dangers and flaws of democracy, particularly a direct democracy in which the “tyranny of the majority” can cause major problems.

We already talked earlier about how the Great Compromise was the agreement that the Electoral College is based on. It gives greater representation to states with higher populations. This makes perfect sense, since a state with more people deserves more of a say. However, it also ensures that these bigger states with highly populated cities do not totally overrule and tyrannize smaller states with lower populations and mostly rural areas.

Take a look at Texas and Montana. Texas is a highly populated state with 29.2 million people, which is why it has a great number of electoral votes (38). With just 1.1 million people, Montana is a state with a very low population compared to Texas, which is why it only has 3 electoral votes. It only makes sense that Texas has much more representation than Montana due to having a much larger population. However, the 3 votes that Montana does receive gives it just enough electoral representation so that those people are not totally ignored by candidates.

The Electoral College deters candidates from solely campaigning in highly populated regions of the country, particularly in big cities and highly urbanized areas. Without the Electoral College, candidates would only focus on winning over the masses in big cities, while totally ignoring vast parts of the country, particularly rural areas where populations are smaller. It holds candidates accountable for winning popular votes across the country as a whole, rather than only focusing on small parts of the country here and there that have large populations.

Keep in mind, the Electoral College has kept our country stable for over 200 years. If it’s not broken, why would we try to fix it?

Now, let’s hear what the other side has to say: abolishing the Electoral College and directly electing the president through a national popular vote.

It is both fair and logical to believe that a democracy should entail a voting system that ensures that each person has an equal vote. However, the Electoral College causes some votes to be worth more than others, depending on which state you happen to live in.

Let’s look at California and Wyoming. California has 55 electoral votes to represent their population of 39.7 million people. Wyoming has 3 electoral votes to represent their population of 581,000 people. After a couple of basic calculations, you can see that each California electoral vote represents approximately 721,000 people, while each Wyoming electoral vote represents approximately 193,000 people. Essentially, each individual electoral vote in Wyoming is worth much more in comparison to California. Now, this is the most extreme example, since California and Wyoming are the most and least populated states, respectively. But this exact same logic applies to all states across the country. Since each state gets 2 senators no matter their population size, small states get an unfair boost to their representation in the Electoral College. This causes the idea of “one person, one vote,” a defining feature of democracy, to be thrown out the window.

Perhaps the biggest flaw of the Electoral College is the “winner takes all” system that applies to nearly every state in the country. Back in 1787, the Framers expected each elector to vote independently for the presidential candidate. The Constitution does not require all of a state’s electoral votes to go to one candidate. However, over time, every state, except Maine and Nebraska, has passed laws that require all of the state’s electoral votes to go to the candidate who wins the popular vote of that state. Electoral independence has been completely wiped out, which has resulted in the “winner takes all” system that does not accurately reflect the divided popular vote of the state. For 48 out of 50 states, the margin of victory of the popular vote has no impact on the final electoral vote count. Whether a candidate wins by a whopping 25 million votes, or by a mere few thousand votes, that candidate receives every electoral vote of that state. If your candidate loses the popular vote of your state, then your vote means nothing. How can we live in a democracy where our vote could have no impact on the final result?

Another flaw of the “winner takes all” system is that candidates can ignore “safe states” and only focus on “swing states.” A safe state is a state that a candidate can rely on winning without investing too much effort into that state, since it regularly leans toward their political party. For example, in recent elections, a Democratic candidate can almost always rely on winning California and receiving all 55 of its electoral votes, while a Republican candidate can almost certainly rely on winning Texas and receiving all 38 of its electoral votes. They can ignore the interests of each individual voter in safe states, since they can rely on winning the state as a whole.

Swing states are states that often flip from one political party to another, meaning that candidates cannot rely on winning that state. These are the states where candidates invest most of their campaign efforts, since they are the only states that ever seem to matter in close elections. It is unfair that a vote in a swing state carries more influence than a vote in a safe state. A national popular vote would allow every vote to carry equal influence across the country.

I value looking at political issues from an objective standpoint to assess the quality of arguments from all sides. I also like to insert my personal opinion into the discussion. I must say that there are quite strong arguments on both sides of this debate, which is why I consider the Electoral College controversy to be one of the more complicated issues in American politics. However, to put it bluntly, I do not support either side! There are too many flaws with both sides for me to comfortably say that I support the current Electoral College or a national popular vote. However, just like in 1787, I believe there is room for a compromise.

I am not, nor have ever been, in favor of abolishing the Electoral College and replacing it with a direct vote at the national level. However, the system that we currently have is in need of serious reform. Here is what I propose:

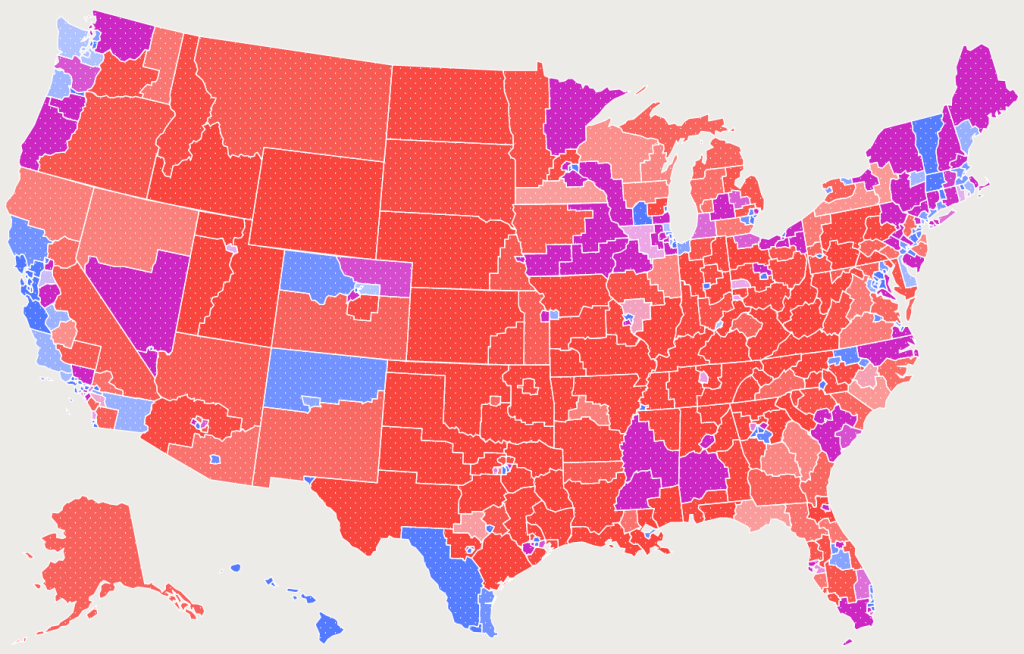

Each state must divide its electoral votes depending on the popular vote of each district. Rather than a statewide popular vote that determines which candidate receives all of the state’s electoral votes, each district would hold their own independent popular vote. Since the number of districts directly corresponds to the number of delegates that each state has in the House of Representatives, each district would have one electoral vote, no matter its size or population.

For example, Ohio has 16 districts, which corresponds to their 16 members in the House of Representatives. There would be a popular vote in each of these 16 districts. The “winner takes all” approach would apply to each district rather than to the state as a whole. If a candidate wins the popular vote of the district, that candidate would receive the one electoral vote for that district, no matter what the margin of victory is. This same method would be applied to every other district in the state.

Let’s say that the Democratic candidate wins the popular vote of 8 districts, while the Republican candidate also wins the popular vote of 8 districts. The Democratic and Republican candidates would each get 8 Ohio electoral votes. But doesn’t Ohio have 18 electoral votes, not 16? Yes, it does. Those 2 remaining electoral votes (which correspond to the 2 senators) would be given to the candidate who wins the statewide popular vote. Let’s say that the Democrat wins the popular vote of all of Ohio. They would then receive those last 2 electoral votes. The electors of Ohio would split their votes by giving 10 to the Democratic and 8 to the Republican.

This system of requiring each state to divide their electoral votes on district lines allows there to be a more fair and accurate reflection of the popular vote of that state, while avoiding the dangers of a national popular vote.

It is essentially a mini-Electoral College within each state. The total number of electoral votes across the country would still be 538, meaning that 270 votes would still be needed to win the White House. The only difference is that each state would be much more divided between red and blue, since the state would be required to divide its electoral votes along district lines. This would eliminate the unfair “winner takes all” approach in which all of the electoral votes of a state are given to a single candidate. My proposed solution would more accurately reflect how close the popular vote of the state actually was.

Not only do I argue that this solution is the most fair and balanced way to elect the president, but I also believe that it is the most feasible to achieve. Abolishing the Electoral College and replacing it with a national popular vote would require a Constitutional amendment. This would need a two-thirds supermajority in both houses of Congress, as well as ratification by a three-quarters supermajority of the state legislatures. This is highly unlikely.

However, if you look closely at the Constitution, it says nothing about how the electors must divide their votes. Instead of a Constitutional amendment at the federal level, the states could pass laws that would require the electors to divide their votes along district lines. This is currently how Maine and Nebraska divide their electoral votes. I believe that it is feasible for other states to follow suit in the future.

This would certainly be no easy task. But after an in-depth analysis of this controversial issue, I believe that this is the best way to achieve a truly free and fair presidential election.